In days gone by, kids played Cowboys and Indians.

How do you “play” a cowboy, anyway? Do you do rope tricks? Maybe hog-tie the family dog? Brand your cat? No, playing cowboy meant shooting Indians.

Playing an Indian had its moments. You got to run around yelling “woo woo woo.” But everyone knew that in the end, you’d wind up dead. Killed by the good guys.

Which brings me to The Canyon of the Dead.

Meet our guide and driver, David, a member of the Navajo tribe. The Navajo call themselves Diné, which means “the people.”

Besides providing historical and cultural information, David piloted our nine person group through some rough territory in this six-wheel-drive Austrian vehicle. It was loud, rough, slow, and pretty entertaining.

We set out at 9:00 from the Thunderbird Lodge. Decent rooms, friendly staff, awful food.

Our first stop was at a small site not named on the map. Access looks difficult, doesn’t it? It was a little easier back in the day because the valley floor was about fifteen feet higher; roughly at the level of the horizontal fissure.

Notice the petroglyphs at the back of the cave.

There are petroglyphs on all three rock faces. How many can you see?

Enjoy the scenery as we travel further into Canyon del Muerto to the Junction ruin.

Back in my Cowboys and Indians days, most of us imagined Indians living in teepees and whooping it up on horseback. Look at where these people – Navajo, Hopi, and their predecessors – lived. This was a bad commute and we’ll see worse later on the tour.

They were hunters and farmers. Their choice to live on a cliff face says, “leave us alone.”

Moving on to the Ledge and Antelope House ruins.

The Ledge ruin is so cute I took three photos. Notice the “awning” over the main building.

The ledge serves as Main Street, or as the British say, High Street. In this case, take that literally.

On to Antelope House and a rest stop.

Here we are at the Antelope House ruin. The leftmost petroglyph gave the ruin its name.

Time for a break!

After our break, we headed deeper into the canyon bound for Mummy and Massacre Caves.

This thousand-foot-tall plateau is called Navajo Fortress Rock. In 1863, the U.S. Government sent Colonel Kit Carson and troops under his command to forcibly remove the Navajo from their homes. The natives refused and about 300 took refuge over the winter atop the plateau. When the soldiers tried to pursue them, the Navajo rolled rocks down on them. Under the cover of darkness, men would sneak down to gather food and water.

In the end, Carson burned the valley orchards and fields, and cut down all the trees forcing the Navajo to surrender, starve, or escape. The survivors were marched 300 miles to Fort Summer in New Mexico.

In February of 1864, Kit Carson ordered the burning and destruction of all Navajo property and homesteads, including crops and livestock. His soldiers killed those Navajos who resisted.

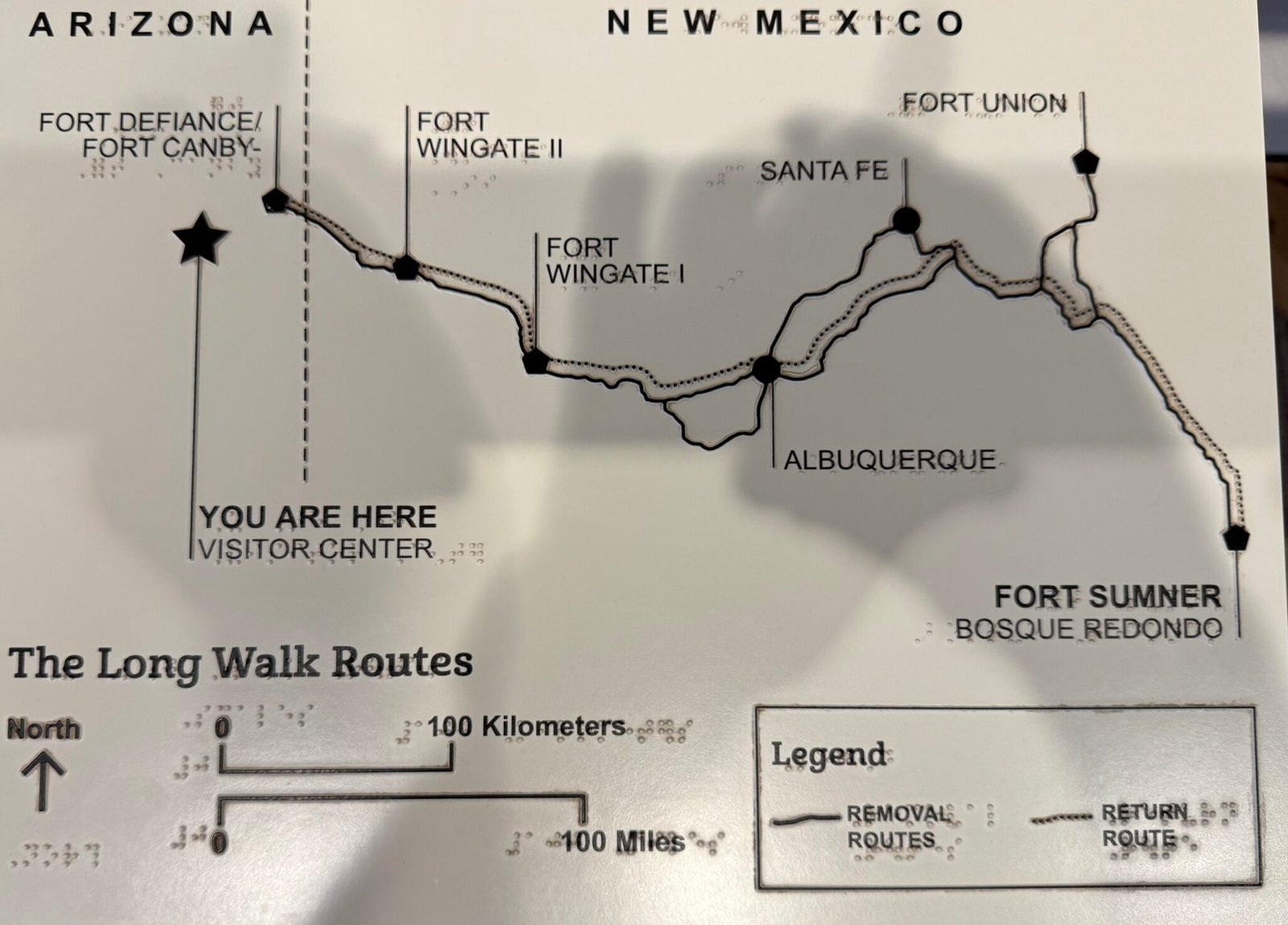

The soldiers told the Navajos to go to Fort Defiance for shelter and food. Thousands came from all directions and gathered there. On March 4, 1864, the assembled Navajos were forced on a nearly 400-mile-long march to Fort Sumner, also called Bosque Redondo. This was the notorious Long Walk of the Navajo.

Many Navajos died on the trek or while held captive at Hwéeldi, the Navajo name for Fort Sumner. The Navajos were imprisoned at the fort for four years, enduring in their incarceration despair and suffering of a kind they had never experienced before. Many died from unfamiliar diseases and starvation.

They lived in crude, dug-out holes in the ground. They tried to farm, but the barren land barely yielded crops. An alkaline stream made them sick but was the only source of water they had. The Navajo call this bleak period of their history “the time of fear and suffering.”

The nearly 400-mile trek from Fort Defiance to Fort Sumner was a brutal forced march through unforgiving landscapes. This map shows the route along which the Navajo were marched.

Some Navajos resisted the order to assemble at Fort Defiance and did not make the Long Walk to Hweeldi. They suffered fear and reprisal as they wandered without homes for as long as six years.

The clearing of the Navajo and The Long Walk that followed is an ugly story. If you want to know more, here is an account that also discusses the events at Massacre Cave.

Leaving Navajo Fortress behind, we continued up the Canyon of the Dead to Standing Cow ruin. This site extends along the base of a cliff. At the rightmost end you can see the cow that give the place its name painted on the wall. There is also the remains of a loom still standing.

Next stop, Mummy Cave.

Mummy Cave got its name from a pair of mummified individuals found in 1880 and at the right-hand end of the site under the vertically striped cliff.

There were no atrocities committed here by the “good guys”, so far as I know.

Lunch time! This is as far into Canyon del Meurto as we will go. We were not able to see nearby Massacre Cave.

This is not Massacre Cave, but it’s similar and should let you picture the events told in the following Navajo story.

When the Spaniards who came looking for gold started killing,” said Sylvia, “the Navajos went up into Massacre Cave to hide, but the Spaniards had an enemy Navajo with them, a scout who showed where the people were going. But there was one lady who was kidnapped and sold as a slave when she was a little girl. When she was a teenager she came back, and she was one of the ones that was hiding with the Navajo people up in the alcove.

They were found out, because there was an elder down at the bottom who was hiding behind a boulder, and they kept telling him, you have to be quiet; but he didn’t listen. He yelled out, and that’s when the Spaniards came around the bend, and found him, and made him tell where the others were hiding. Then the Spaniards killed the Navajo elder, and they even killed the scout, because they thought the scout had turned against them. Then they went up, and they started shooting, but some of the Navajos pushed boulders down, and they killed a lot of the enemies, and stopped them from climbing into the cave.

The Spaniards who were up above started shooting into the alcove, and the lady got knocked unconscious. When she woke up she saw some of the soldiers in the alcove, and she says, ‘If by any chance, if I’m going to die, I don’t want to die at the hands of these enemies. If I’m going to die, let me take one of them with me.’ And so she looked ahead, and there was a soldier standing at the edge, so without any warning, and without anybody seeing her, she got up really fast and ran at the enemy, and they both fell off the edge to their death. So in Navajo, we don’t call it Massacre Cave. The name Massacre Cave was given by the archaeologists. For us, we say, ‘Two that fell off the Cliff,’ and that’s the name of that place.

My thanks to rcquinn.com for relating this story.

We began the long drive back down Canyon del Muerto after lunch. We’re bound for the junction where Canyon de Chelly forks off to the south. We’ll make a relatively short excursion up the southern fork to view the White House ruin.

This is the White House. It’s the only site we visited in Canyon de Chelly.

Construction of the buildings at the White House site began around 1070, and the place is thought to have been abandoned in the late 1300s. The name derives from a whitish band across the nearby cliffs.

If you come to Canyon de Chelly hoping to hike, you’ll be disappointed. The only place visitors were allowed to walk without a guide was the trail from the White House overlook to the ruins. Both overlook and trail have been closed for several years thanks to evil doers vandalizing cars while hikers were elsewhere.

You can read the story and see what you’re missing in this article.

The tour used to continue up the valley to visit Spider Rock. I’m not sure why it no longer does.

After seven hours rattling around in our assault vehicle, it was time to head back to Thunderbird Lodge.